Have researchers in Switzerland discovered a new chocolate?

Switzerland’s rise as a chocolate hub was built on the commodity trade of colonial goods, which included cocoa and involved slavery."

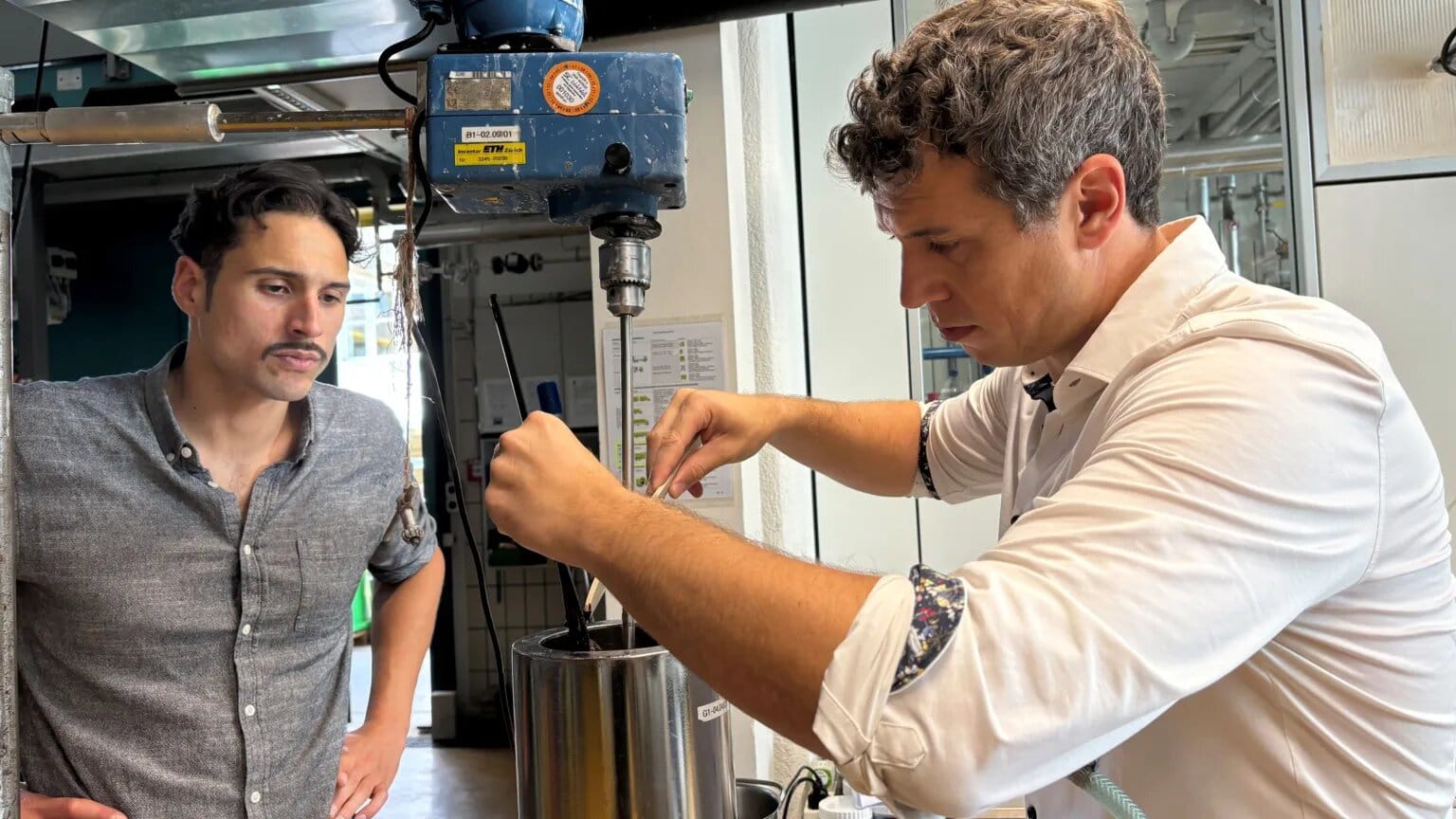

The new approach to chocolate-making developed by scientists at Zurich’s Federal Institute of Technology represents a significant innovation in the industry.

Traditionally, cocoa producers have only used the beans of the cocoa fruit to make chocolate, discarding the rest of the fruit. This method not only wastes a substantial part of the fruit but also relies on adding sugar to the chocolate.

Kim Mishra and her team have pioneered a method that utilizes the entire cocoa fruit, including the pulp, juice, and husk (endocarp), creating a more sustainable and potentially healthier product.

By incorporating all parts of the cocoa fruit, the process could reduce waste and offer a richer, more complex flavor profile.

Additionally, the absence of added sugar in their chocolate aligns with growing consumer preferences for healthier options.

This development not only enhances the sustainability of chocolate production but also introduces a new dimension to the chocolate-making process, potentially leading to unique flavors and textures in the final product.

"You need to innovate to keep your product category relevant," says Mr. Mishra. "Otherwise, you'll just produce average chocolate."

Mr. Mishra’s project is in collaboration with KOA, a Swiss start-up focused on sustainable cocoa cultivation.

Anian Schreiber, co-founder of KOA, believes that utilizing the entire cocoa fruit could address numerous issues in the cocoa industry, from the rising cost of cocoa beans to the persistent poverty faced by cocoa farmers.

"Instead of competing over portions of the cake, you make the cake larger and benefit everyone," he explains.

"Farmers earn significantly more by using cocoa pulp, and crucial industrial processing occurs in the country of origin. This creates jobs and distributes value locally."

Mr. Schreiber criticizes the traditional chocolate production model, where farmers in Africa or South America sell their cocoa beans to large chocolate companies in affluent countries, as "unsustainable."

This model is also scrutinized by a new exhibition in Geneva that examines Switzerland’s colonial past.

Despite Switzerland never having had its own colonies, chocolate historian Letizia Pinoja points out that Swiss mercenaries enforced colonial regimes and Swiss ship owners were involved in the slave trade.

Geneva, in particular, is linked to some of the most exploitative periods of the chocolate industry. "Geneva has been a hub for commodity trade since the 18th century, with cocoa arriving there and subsequently spreading throughout Switzerland to produce chocolate," Pinoja says.

"Switzerland’s rise as a chocolate hub was built on the commodity trade of colonial goods, which included cocoa and involved slavery."

Today, the chocolate industry is more regulated.

Producers are required to monitor their supply chains to prevent child labor, and from next year, all chocolate imported into the European Union must ensure no deforestation occurred in the cultivation of the cocoa used.

However, Roger Wehrli, director of Chocosuisse, the Swiss chocolate manufacturers’ association, notes that child labor and deforestation issues persist, particularly in Africa.

He worries that some producers might be moving their operations to South America to sidestep these challenges.

"Does this resolve the problem in Africa? No. It would be better for responsible companies to stay in Africa and work to improve conditions there," Wehrli says.

He finds the new Zurich-developed chocolate "very promising," noting that using the entire cocoa fruit can result in better prices and is both economically beneficial for farmers and ecologically advantageous.

Anian Schreiber highlights the environmental impact of chocolate production, noting that a third of all farm produce "never ends up in our mouths." The situation is even worse for cocoa when only the beans are used, leaving the rest of the fruit to rot.

"It's like throwing away the apple and only using the seeds," he says, referring to the current practice of discarding most of the cocoa fruit.

Food production significantly contributes to greenhouse gas emissions, so reducing food waste could aid in combating climate change.

While chocolate itself is a niche luxury and might not be a major factor, both Mr. Schreiber and Mr. Wehrli see it as a potential starting point for broader change.

In the laboratory, however, key questions remain. How much will this new chocolate cost? And, most importantly, without sugar, what does it taste like?

From this chocolate-loving correspondent’s perspective, the taste is surprisingly pleasant—a rich, dark flavor with a touch of cocoa bitterness that pairs well with after-dinner coffee.

The cost might pose a challenge due to the global influence of the sugar industry and its subsidies. "The cheapest ingredient in food will always be sugar as long as we subsidize it," says Kim Mishra, noting that a tonne of sugar costs $500 or less.

In contrast, cocoa pulp and juice are more expensive, so the new chocolate is likely to be pricier for now.

Despite this, chocolate producers in cocoa-growing regions, from Hawaii to Guatemala and Ghana, have already reached out to Mr. Mishra for details about the new production method.

In Switzerland, some of the larger chocolate producers, such as Lindt, are beginning to incorporate the entire cocoa fruit in their products, rather than just the beans.

However, none have yet fully eliminated sugar from their chocolate.

"We need to find bold chocolate producers who are willing to test the market and contribute to a more sustainable chocolate industry," says Mr. Mishra. "Then we can disrupt the system."

Switzerland, with its annual production of 200,000 tonnes of chocolate worth around $2 billion, could be the place where these innovative producers emerge.

At Chocosuisse, Roger Wehrli is optimistic about the future of chocolate.

"I believe chocolate will continue to taste fantastic," he asserts. "And with the growing world population, demand will increase."

When asked if Swiss chocolate will remain a staple, he confidently replies, "Obviously."