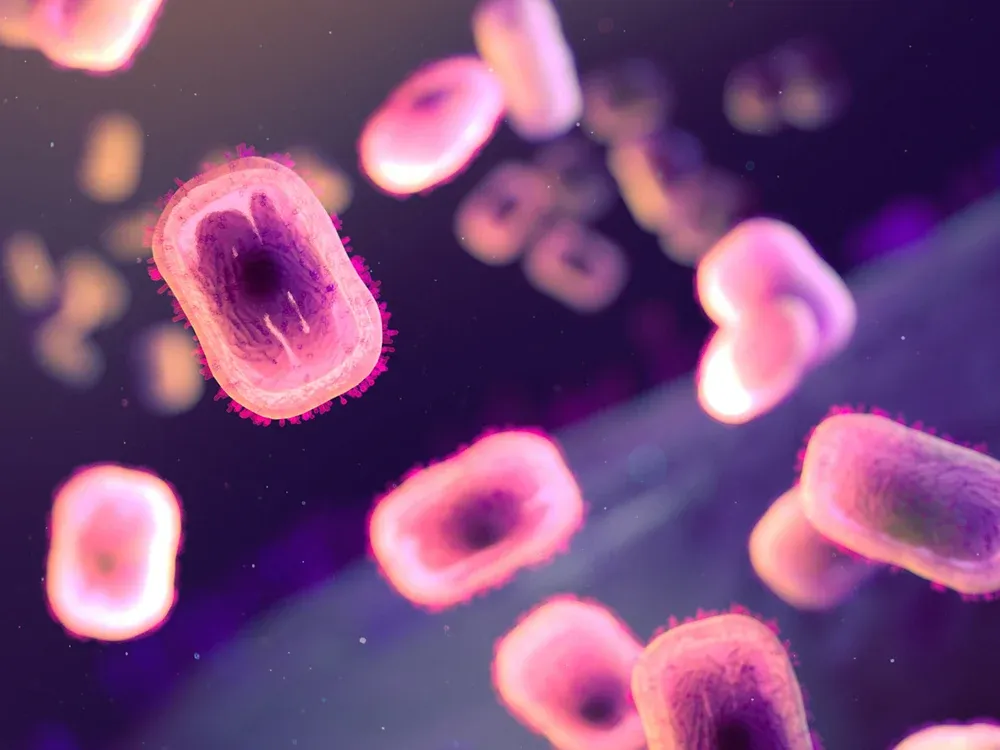

The WHO Declares Mpox a ‘Public Health Emergency of International Concern’

There is also evidence this strain is more deadly, with mortality rates of between three and five per cent, which considerably exceeds the average mortality rate of COVID-19.

On Aug. 14, the World Health Organization classified the mpox virus, which is surging across several African countries, as a “public health emergency of international concern.” This action will help mobilize global and regional public health resources to better monitor and respond to the threats posed.

Naturally, in the wake of COVID-19, the classification has many people worried we’re about to relive the collective trauma of lockdowns and fears of acquiring a potentially deadly virus. As an epidemiologist who studies the intersection of infectious diseases and social life, I share these concerns, but, at this point, I believe the WHO’s announcement should raise caution, not cause panic.

What is mpox and how does it spread?

Mpox, once referred to as monkeypox, is a virus that causes flu-like symptoms and skin blisters across the body. Fortunately, the virus is mostly spread through direct contact with infected lesions or bodily fluids, or through contaminated materials like bedding. This means it is not typically as contagious as respiratory diseases such as COVID. However, it can also spread through respiratory droplets, although this typically occurs only with prolonged close contact in areas with limited ventilation.

These characteristics explain why historically mpox outbreaks have typically been limited to densely interconnected sexual networks and in venues where physical contact may be prolonged, such as in night clubs.

However, the current situation in Africa is showing that some of these characteristics are changing. In the Democratic Republic of Congo and neighbouring countries, it appears that a more deadly, more virulent version of the virus — arising from a strain referred to as Clade 2 — is taking hold. This is evidenced by the fact that several African countries that had not previously seen transmission are now seeing increased spread.

As well, public health officials note transmission in children, suggesting that this more virulent form may require less physical contact than we observed in the transmission of Clade 1, which caused a global outbreak in 2022.

There is also evidence this strain is more deadly, with mortality rates of between three and five per cent, which considerably exceeds the average mortality rate of COVID-19.

With all this in mind, it’s natural to ask, “Should we be worried?”

Understanding risks in Canada

At the moment, the WHO’s actions indicate that the international public health community should pay attention and prepare for a possible large-scale international outbreak of mpox — something it has failed to do in recent decades.

Most importantly, its declaration allows for enhanced global collaboration to monitor the situation in the Democratic Republic of Congo and surrounding countries. It also makes it possible to prioritize the availability of vaccines in those regions to bring viral transmission under control.

We are fortunate, in Canada, to have an excellent public health surveillance system and to have some access to vaccine supplies for mpox. The existing mpox vaccines are safe and effective. Currently, their use is prioritized for high-risk populations, such as gay and bisexual men and people employed in sex work.

If transmission begins in other populations, it is likely that production of the mpox vaccine could be increased and supplies would be more broadly available to meet demand and need. But it is important to note that redirecting those vaccines will limit their availability to African countries that lack the necessary biomanufacturing capacity to produce them.

As well, Canada is fortunate to have world-class medical facilities that can provide necessary treatment and care to people who might experience vulnerability to the mpox virus. All of these factors suggest that Canada will be well equipped to respond to potential outbreaks, provided, of course, that we all do our part.