Thinking the 'unthinkable': NATO wants Canada and allies to gear up for a conventional war

NATO's call for defence industrial strategies pulls Canada into a conversation it has avoided for decades

NATO has announced that it expects its member countries to develop national strategies to enhance the capacity of their individual defense industry sectors, a challenge that Canada has grappled with—or largely avoided—for decades.

During the NATO leaders summit in Washington in July, alliance members reached an agreement to formulate strategies aimed at strengthening their domestic defense materiel sectors and to share these strategies among themselves. However, this new policy received scant attention, overshadowed by discussions about defense spending and support for Ukraine.

Federal officials are just beginning to assess the implications of this policy and the potential burden it could impose on the government and Canada’s defense industry. CBC News has discovered that Ottawa lacks substantial institutional knowledge or Cold War-era frameworks to draw upon. For years, the federal government has not had a comprehensive plan to mobilize the country, federal institutions, and the economy for conventional warfare—such as that being fought in Ukraine today.

Several experts, including a former high-ranking national security official, defense analysts, and a retired senior military leader, indicate that Canadians and their governments have largely ignored these considerations for the past 30 years. Now, NATO is emphasizing their importance.

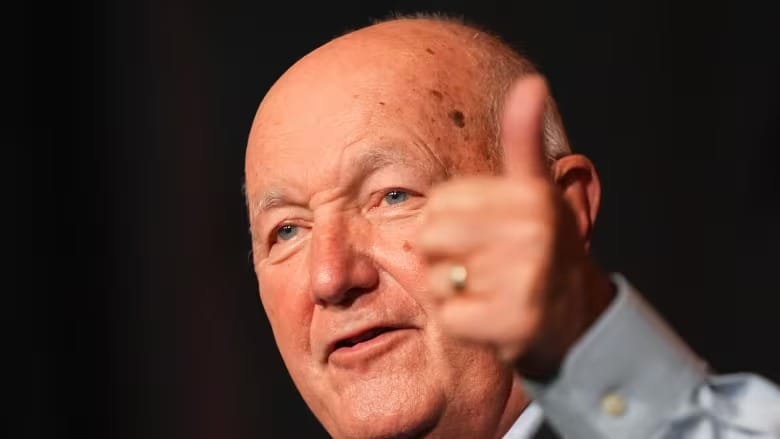

Vincent Rigby, a former national security and intelligence adviser to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, stated, "This is something we should definitely be thinking about, [but] I get why we kind of stopped thinking about this post-Cold War," referencing the years of relative peace following the Soviet Union's collapse. In light of Russia's invasion of Ukraine, he assesses the chances of Canada being drawn into a significant regional conflict in the coming years as 50-50.

The possibility of an armed conflict involving Western allies and Russia or China looms over Canada, Rigby noted, yet the country still lacks a national security strategy, formal foreign policy, or a defense industrial policy. He remarked, "Given the state of the world, we have to have contingency plans in place," stressing that the next major conflict could involve a series of regional wars in which Canada would participate as a Western ally.

The Department of National Defence was vague when asked about actions being taken in response to NATO’s new commitment, mainly referencing the revised national defense policy, which pledges that the Canadian Armed Forces will be capable of deploying "highly capable forces to meet crisis situations at home and abroad."

The department has existing plans for mobilizing troops in the event of war. Historically, the defense department categorized mobilization into four phases, as outlined in the 1994 Defence White Paper. The initial three phases focused on maintaining and training forces and gradually mobilizing and equipping reserve troops to bolster the army, navy, and air force. Each branch had clearly defined federal plans.

The fourth phase involved "full national mobilization," which would encompass all aspects of Canadian society and would be activated in the event of war and the declaration of the Emergencies Act. However, the 1994 document indicated that the federal government had no detailed plan for such a scenario, even though officials acknowledged that it was "prudent to have 'no-cost' plans ready for total national mobilization," despite the relative international stability anticipated at the time.

Retired Lieutenant-General Guy Thibault, a former vice chief of the defense staff, reported that no comprehensive mobilization plan was ever created. He noted that many initiatives "withered on the vine" during the 1990s as the federal government underwent significant budget cuts, leaving the military scrambling to maintain essential operations.

"We were all focused on really squeezing as much juice as we could out of an ever-decreasing size of the force," said Thibault, who retired in 2016 and currently heads the Conference of Defence Associations Institute. Although the 2014 Russian annexation of Crimea was a wake-up call, Thibault pointed out that even then, discussions about "mobilizing society towards scenarios that were kind of unthinkable" were absent.

The federal government's new defense policy recognizes the necessity of strengthening Canada’s defense industrial base. However, since Russia's invasion of Ukraine, the government has struggled to increase even basic ammunition production.

There is a long-standing reluctance within the federal government to collaborate closely with defense contractors, according to Christyn Cianfarani, president of the Canadian Association of Defence and Security Industries. "The Canadian government has long been an outlier internationally in its unwillingness to work in partnership with its domestic defense industry," she told the House of Commons defense committee on Tuesday.

With this new policy, NATO has officially recognized that each member's contribution to a steady supply of arms and munitions represents "a new element of NATO burden-sharing."

While serving as chief of the defense staff, Wayne Eyre repeatedly warned Parliament and the public that Canada’s defense industry is ill-equipped for potential future challenges and that munitions manufacturers need to adopt a "war footing." This shift has yet to occur.

"We are not on a war footing whatsoever," Cianfarani told the four-party Commons committee. "I mean, we are just not in a state of high alert, and we are not operating with a sense of urgency that we see other partners... operating with."

Steve Saideman, a professor holding the Paterson Chair in International Affairs at Carleton University, expressed skepticism about the government's commitment to meeting NATO's two percent defense spending benchmark, questioning the level of effort it will apply to the new defense industrial initiative. "I think for the past 30-plus years, we've all been quite happy not to think about such things," Saideman remarked, noting that this mindset has persisted under both Liberal and Conservative governments.

The rarely invoked Defence Production Act grants the defense minister extraordinary powers during wartime, but Saideman noted, "we don't have a good mechanism, at least as far as I can tell, for having cooperation between industry and the government so that they can make commitments to be able to turn a switch and change things around."

Given the significant losses of personnel and equipment Ukraine has faced while fending off the Russian invasion, Saideman hopes both the federal government and the defense industry are taking note. "If we got into a serious shooting match with either China or Russia, we'd lose ships, and that would require replacement faster than the replacement ships that we've been doing right now," he explained, referencing the navy's protracted frigate replacement program.

"That goes for planes, that goes for everything. But one of the challenges is we have to figure out something really hard, which is, how do we do quantity in the 21st century? Our procurement has been about quality, about getting the best possible equipment, and having a few of those around that can do as many things as possible."

Saideman expressed doubt about Canada’s current capacity to mobilize for war as it did during World War II. "I just don't see Canada having that capacity," he asserted.

Military historian Sean Maloney noted that even during the Cold War, federal officials were not contemplating mobilization for conventional warfare. "In the 1950s, the dominant war plans with the U.S. and Canada within NATO all revolved around nuclear weapons," Maloney explained, pointing out that the Conservative government at the time expected any conflict with the Soviet Union to escalate to nuclear warfare, making defense industries primary targets.

Maloney suggested that this mindset explains the historical lack of planning. However, in light of the ongoing war in Ukraine, Ottawa can no longer claim ignorance. "The idea that everything's going to be a runaway nuclear escalation has been proven false over the past two years," he stated, adding that like Saideman, he doubts Canada could replicate its World War II mobilization, either institutionally or socially.

"We're drowning in red tape. The level of regulation stifles innovation. It stifles creativity," Maloney remarked, criticizing the federal government’s overall approach to industry. "The population is so divided about what it wants, or what it thinks it wants, it can't process the strategic realities we're dealing with right now."

Maloney emphasized that Ukraine's experience highlights the necessity of national will in conflict. "It is absolutely fundamental to any effort that you're talking about," he asserted. "And it does not exist in this country, either at the elected political level, in the bureaucracy or the population."