Why Does Poilievre Keep Saying the Nazis Were Socialists?

A right-wing interpretation of history links fascism and socialism. How accurate is it?

Canadians, despite their political differences, generally agree that the Nazi regime and Soviet-style communism were both brutal and repressive. However, opinions on the term "socialism" tend to vary based on political perspectives.

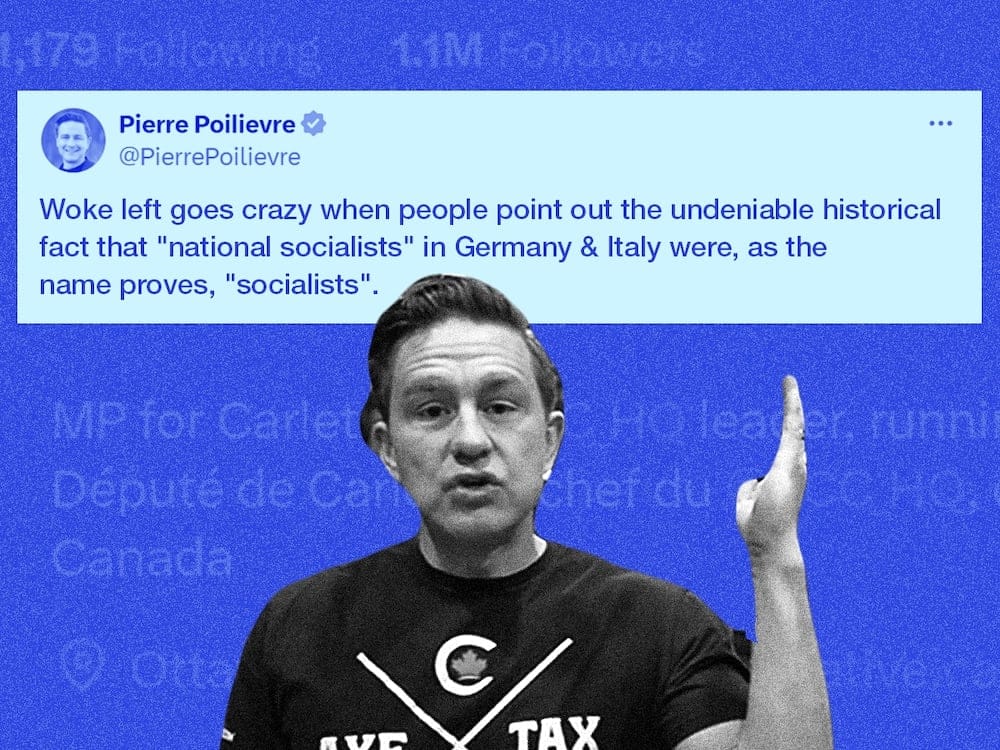

Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre has repeatedly emphasized the "socialist" aspect of the Nazi Party's full name, the National Socialist German Workers’ Party. In his social media posts, he has grouped fascism, communism, and socialism together, referring to fascism as a "socialist ideology." On Black Ribbon Day, which marks the 1939 agreement between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany to divide Eastern Europe, Poilievre wrote:

“On the 85th anniversary of Black Ribbon Day, we remember the victims of Soviet Socialism & National Socialism (Nazism). May we never forget the countless atrocities committed by these socialist ideologies, and may we honour those who fought to liberate Europe. Canada must always stand against socialism for freedom and democracy.”

This isn’t the first time Poilievre has equated Nazism with socialism. In 2021, he claimed on social media that “national socialists” in Germany and Italy were socialists, arguing that fascism, socialism, and communism glorify the state at the expense of individuals, with horrific consequences. These comments have sparked strong backlash, including criticism from conservatives like Vancouver-based real estate developer Bob Ransford, who stated:

“As a long-time Conservative who has campaigned against socialism in Canada, I am appalled at your effort to equate democratic socialism in our country with Nazism. Shame on you! You have dragged national politics down to a new level.”

Historians have long debated the ideological roots of Nazism. While the Nazi Party initially branded itself as socialist to attract working-class support, its policies prioritized nationalism, militarism, and racial supremacy. Heidi Tworek, a history professor at the University of British Columbia, explains that early Nazi programs contained anti-big-business and pro-worker elements. However, once in power, the Nazis frequently contradicted their own rhetoric, collaborating with large private companies, particularly in industries like arms manufacturing. Tworek notes that antisemitism and racism remained the central ideologies defining Nazi rule.

American historian Robert Paxton, in his analysis of fascism, argued that while early Nazi rhetoric contained anti-capitalist themes, the party abandoned those ideas once it gained power. Similarly, historian Ronald J. Granieri has highlighted that Nazism’s focus was not on controlling the means of production or redistributing wealth but on enforcing a rigid social and racial hierarchy.

The suggestion that fascism is a form of socialism often omits or downplays Nazism’s deeply rooted racial ideology, says Tworek. This omission, especially when simplified for social media, can provoke strong reactions from those who feel the focus on socialism obscures the role of antisemitism and racism in Nazi ideology.

Political scientist David Moscrop describes this framing as an extreme form of "anti-statism," where right-wing rhetoric ties socialism to totalitarian regimes like Nazism to discredit the role of the state in governance. Moscrop points out that modern social democracies, which combine social programs with capitalist economies, stand in stark contrast to authoritarian models like communism or fascism.

In today’s polarized political climate, terms like "fascist," "communist," and "socialist" are often used as rhetorical weapons by both sides. This trend risks undermining meaningful political discourse. Moscrop warns that such rhetoric, whether from the left or the right, poisons debate, radicalizes communities, and shifts the focus away from solving real issues.

He encourages voters to critically evaluate the language used by politicians, noting that equating socialism with Nazism is more about stoking fear and division than addressing substantive policy challenges.